H.G. Wells is a household name, known for his significant contributions to the Western canon, having penned such classics as The Time Machine, The Invisible Man, and The War of The Worlds. For that legacy alone, Wells could arguably be named the father of science-fiction. At a minimum, he was a significant inspiration on generations of youthful imaginations, mine included. In fact, I can recall an almost seamless transition in my life, when I went from playing army men in the grass to consuming Wells’ classics, most favourably those aforementioned titles. Admittedly, I’ve never grown out of either of these affections and have very fond memories of both; these were like a proverbial sandbox for my mind to roam within. And finally like father, like son — I’ve now had the privilege of watching my own son grow through nearly the same trajectory.

But what about H.G. Wells’ legacy as the father of wargames? Yes, you read that right! The pacifist, H.G. Wells. To be more accurate I should qualify that those little green and tan plastic men of my youth would have been foreign to Wells, who would have been more familiar with tin soldiers. But it was with those little tin soldiers that H.G. Wells would draft the literal rule book on how to play army men. I’d be remiss if I didn’t here give a hearty shout-out to my friend Christopher Watts, author of The Ravenstones series, who first introduced me to Wells’ mutual love playing army men.

Wells’ rulebook, Little Wars he called it, is chock full of amusing nuggets, including philosophical musings on the nature of war and human sacrifice. And this odd manual has served as the prime inspiration behind my similarly-titled contribution The Little War, which can be found in the upcoming anthology, The Boy’s Book of Adventure.

But Little Wars itself is called “the game of kings,” though it is meant for players in an inferior social position. As Wells so Victorianly framed it, his game “can be played by boys of every age from twelve to one hundred and fifty—and even later if the limbs remain sufficiently supple—by girls of the better sort, and by a few rare and gifted women.”

On his inspiration, Wells wrote:

“… in all ages a certain barbaric warfare has been waged with soldiers of tin and lead and wood, with the weapons of the wild, with the catapult, the elastic circular garter, the peashooter, the rubber ball, and such-like appliances—a mere setting up and knocking down of men. Tin murder. The advance of civilisation has swept such rude contests altogether from the playroom...” [But] The beginning of the game of Little War, as we know it, became possible with the invention of the spring breechloader gun. This priceless gift to boyhood appeared somewhen towards the end of the last century, a gun capable of hitting a toy soldier nine times out of ten at a distance of nine yards. It has completely superseded all the spiral-spring and other makes of gun hitherto used in playroom warfare. These spring breechloaders are made in various sizes and patterns, but the one used in our game is that known in England as the four-point-seven gun. It fires a wooden cylinder about an inch long, and has a screw adjustment for elevation and depression. It is an altogether elegant weapon. It was with one of these guns that the beginning of our war game was made.”

Today, H.G. Wells’ rule book is available in its entirety online with thanks to Project Gutenberg. But for enjoyment sake, and to whet your appetite, I have provided some colourful excerpts from Wells’ introduction below, with the hopes that you too will be inspired to let your mind roam in the sandbox — from time to time.

“The present writer had been lunching with a friend—let me veil his identity under the initials J.K.J.—in a room littered with the irrepressible debris of a small boy's pleasures. On a table near our own stood four or five soldiers and one of these guns. Mr J.K.J., his more urgent needs satisfied and the coffee imminent, drew a chair to this little table, sat down, examined the gun discreetly, loaded it warily, aimed, and hit his man. Thereupon he boasted of the deed, and issued challenges that were accepted with avidity.…

He fired that day a shot that still echoes round the world. An affair—let us parallel the Cannonade of Valmy and call it the Cannonade of Sandgate—occurred, a shooting between opposed ranks of soldiers, a shooting not very different in spirit—but how different in results!—from the prehistoric warfare of catapult and garter. "But suppose," said his antagonists; "suppose somehow one could move the men!" and therewith opened a new world of belligerence.

The matter went no further with Mr J.K.J. The seed lay for a time gathering strength, and then began to germinate with another friend, Mr W. To Mr W. was broached the idea: "I believe that if one set up a few obstacles on the floor, volumes of the British Encyclopedia and so forth, to make a Country, and moved these soldiers and guns about, one could have rather a good game, a kind of kriegspiel."...

Primitive attempts to realise the dream were interrupted by a great rustle and chattering of lady visitors. They regarded the objects upon the floor with the empty disdain of their sex for all imaginative things.

But the writer had in those days a very dear friend, a man too ill for long excursions or vigorous sports (he has been dead now these six years), of a very sweet companionable disposition, a hearty jester and full of the spirit of play. To him the idea was broached more fruitfully. We got two forces of toy soldiers, set out a lumpish Encyclopaedic land upon the carpet, and began to play. We arranged to move in alternate moves: first one moved all his force and then the other; an infantry-man could move one foot at each move, a cavalry-man two, a gun two, and it might fire six shots; and if a man was moved up to touch another man, then we tossed up and decided which man was dead. So we made a game, which was not a good game, but which was very amusing once or twice. The men were packed under the lee of fat volumes, while the guns, animated by a spirit of their own, banged away at any exposed head, or prowled about in search of a shot. Occasionally men came into contact, with remarkable results. Rash is the man who trusts his life to the spin of a coin. One impossible paladin slew in succession nine men and turned defeat to victory, to the extreme exasperation of the strategist who had led those victims to their doom. This inordinate factor of chance eliminated play; the individual freedom of guns turned battles into scandals of crouching concealment; there was too much cover afforded by the books and vast intervals of waiting while the players took aim. And yet there was something about it.... It was a game crying aloud for improvement.

Improvement came almost simultaneously in several directions. First there was the development of the Country. The soldiers did not stand well on an ordinary carpet, the Encyclopedia made clumsy cliff-like "cover", and more particularly the room in which the game had its beginnings was subject to the invasion of callers, alien souls, trampling skirt-swishers, chatterers, creatures unfavourably impressed by the spectacle of two middle-aged men playing with "toy soldiers" on the floor, and very heated and excited about it. Overhead was the day nursery, with a wide extent of smooth cork carpet(the natural terrain of toy soldiers), a large box of bricks—such as I have described in Floor Games—and certain large inch-thick boards.

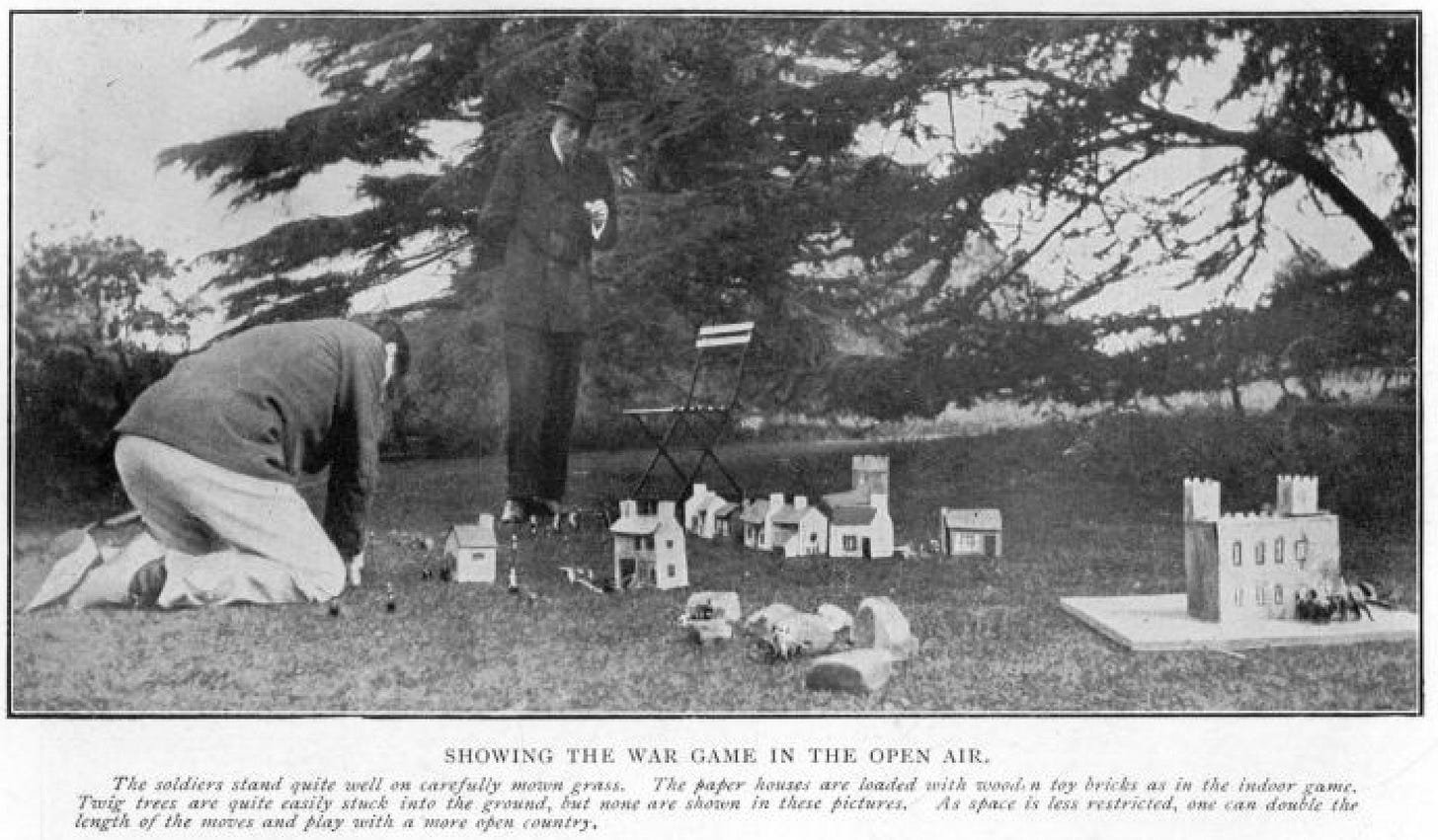

It was an easy task for the head of the household to evict his offspring, annex these advantages, and set about planning a more realistic country. (I forget what became of the children.) The thick boards were piled up one upon another to form hills; holes were bored in them, into which twigs of various shrubs were stuck to represent trees; houses and sheds (solid and compact piles of from three to six or seven inches high, and broad in proportion) and walls were made with the bricks; ponds and swamps and rivers, with fords and so forth indicated, were chalked out on the floor, garden stones were brought in to represent great rocks, and the "Country" at least of our perfected war game was in existence. We discovered it was easy to cutout and bend and gum together paper and cardboard walls, into which our toy bricks could be packed, and on which we could paint doors and windows, creepers and rain-water pipes, and so forth, to represent houses, castles, and churches in a more realistic manner, and, growing skilful, we made various bridges and so forth of card. Every boy who has ever put together model villages knows how to do these things, and the attentive reader will find them edifyingly represented in our photographic illustrations.”

The rule book goes on to provide examples of actual battles Wells and his friends played through, and is paired with many lovely photographs which showcase the dedication that they gave to this little side-project. But for now, I’d be remiss if I didn’t plug my own work. If you wish to support my writing directly, please consider reading and reviewing Frog of Arcadia. Independent authors, like me, rely on reviews on major platforms like Amazon and Good Reads. So help get the word out.

H. G. certainly went all in on playing with toy soldiers. I love the idea of building each country with the various pieces and then having the soldiers engage in combat with one another. War simulations will always be around in one form or another, for entertainment and simply for learning more about war and battles as you never know when you'll find yourself involved in one, no matter how much you avoid them. Great post, Blake.

Blake, Glad to see you're back writing and found the HG Wells's Little Wars as delightful as I did. And thanks for the shout-out. Cheers, Chris